ff. 92v-94r: The Kings of England sithen William Conquerour

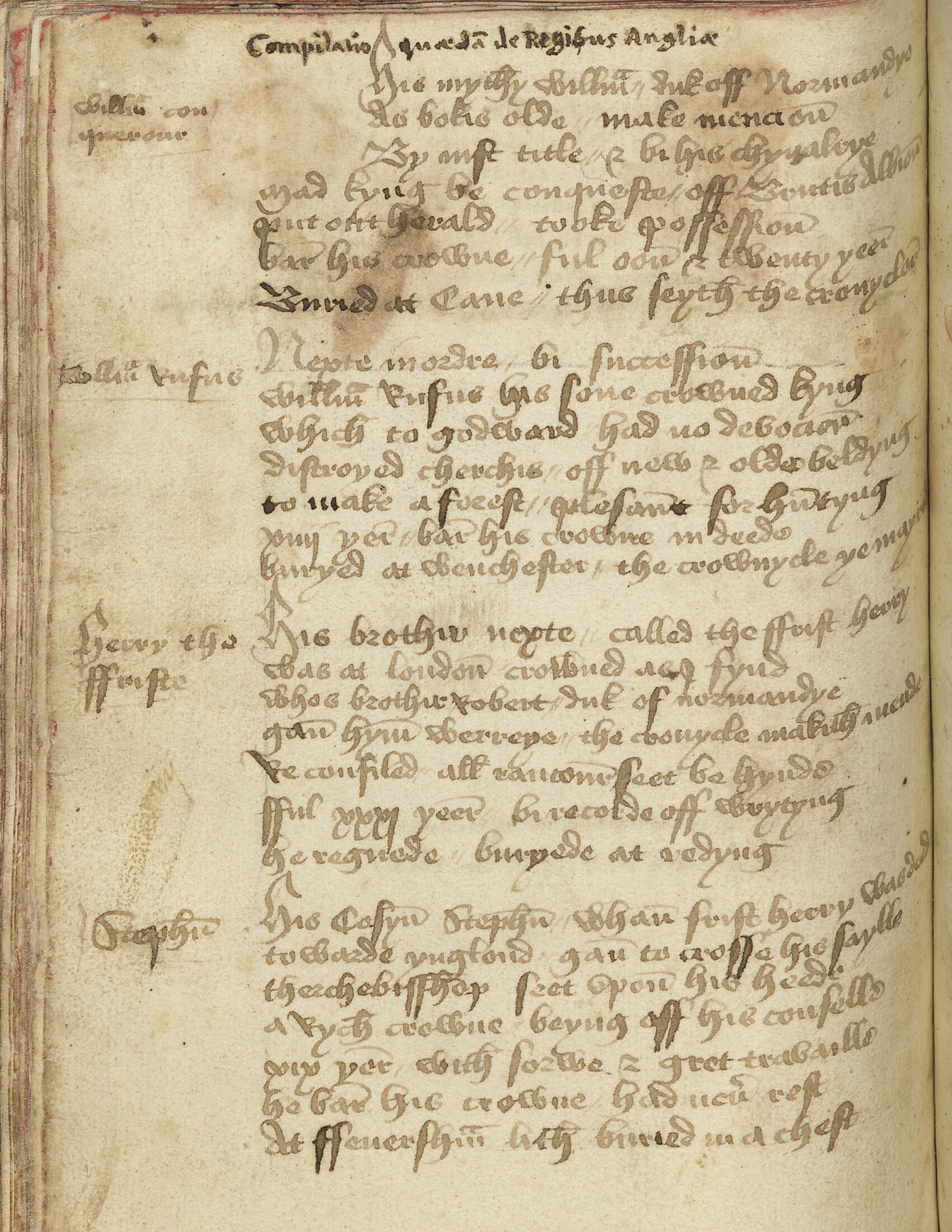

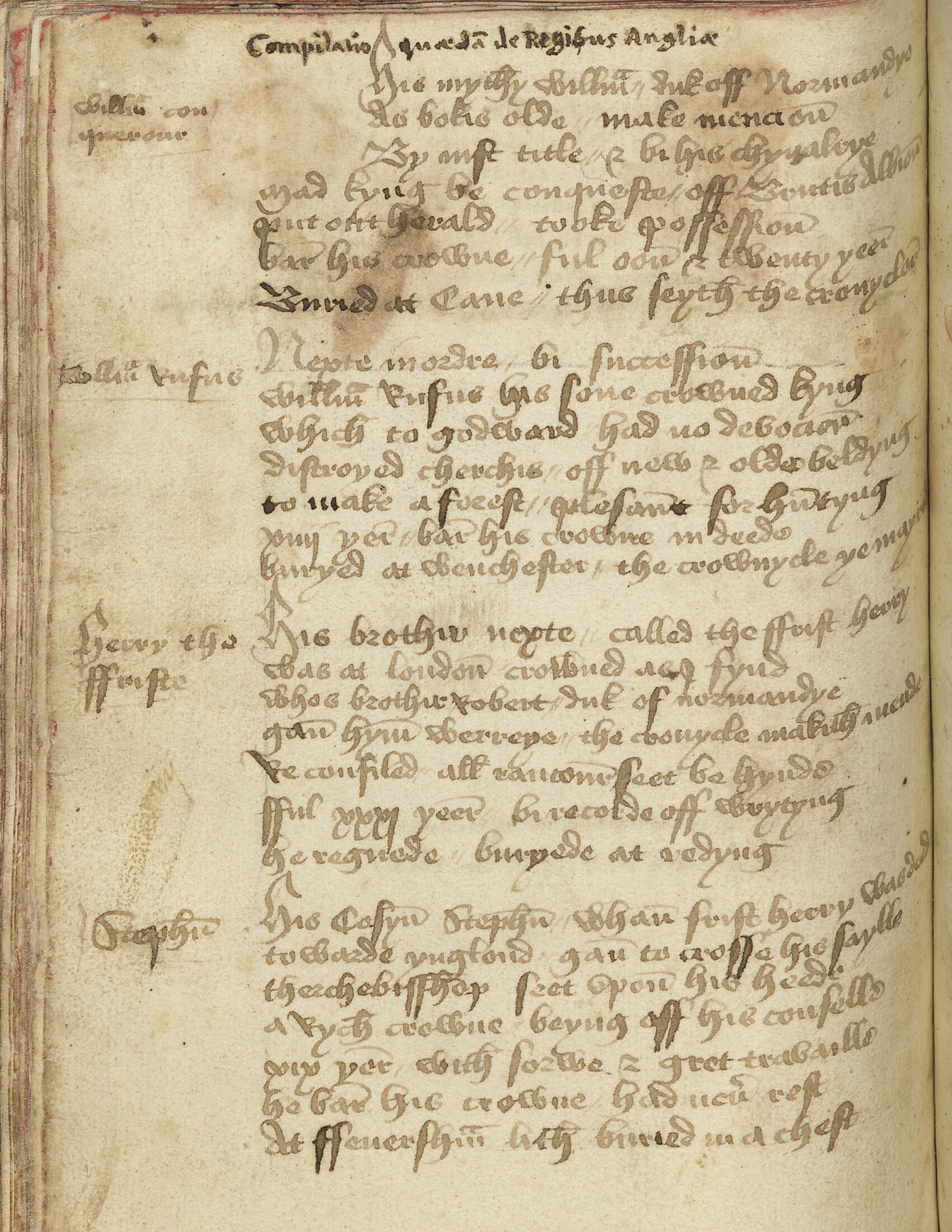

Compilatio quæda(m) de Regibus Angliæ

will(i)am con querour His mythy will(i)am // duk off Normandye

As bokis olde // make mencion

By iust title // (and) bi his chyualrye

mad kyng be conqueste // off Brutis Albion

put out herald // tooke possession

bar his crowne // ful oon (and) twenty yeer

Buried at Cane // thus seyth the cronyclar

[[wi]]ll(i)am Rufus Nexte in ordre // bi succession

will(i)am Rufus his sone crowned kyng

which to godward had no devocion

distroyed cherchis // off new (and) olde beldyng

to make a forest // plesant for hu(n)tyng

xiiij yer // bar his crowne in deede

buryed at wenchester // the crownycle ye may †rede†

Herry the His brothir nexte // called the ffrist herry

ffriste was at london crowned as I fynd

whos brothir Robert // duk of normandye

gan hym werreye // the cronycle makith mende

Reconsiled all rancour seet be hynde

fful xxxj yeer // bi recorde off wrytyng

he regnede // buryede at redyng

Steph(e)n His Cosyn Steph(e)n // whan frist herry was ded

towarde ynglond // gan to crosse his saylle

therchebisshop seet vpon his heede

a Rych crowne // beyng off his conselle

xix yer // with sorwe (and) gret travaille

he bar his crowne // had neu(er) rest

at ffeuersham lith buried in a chest

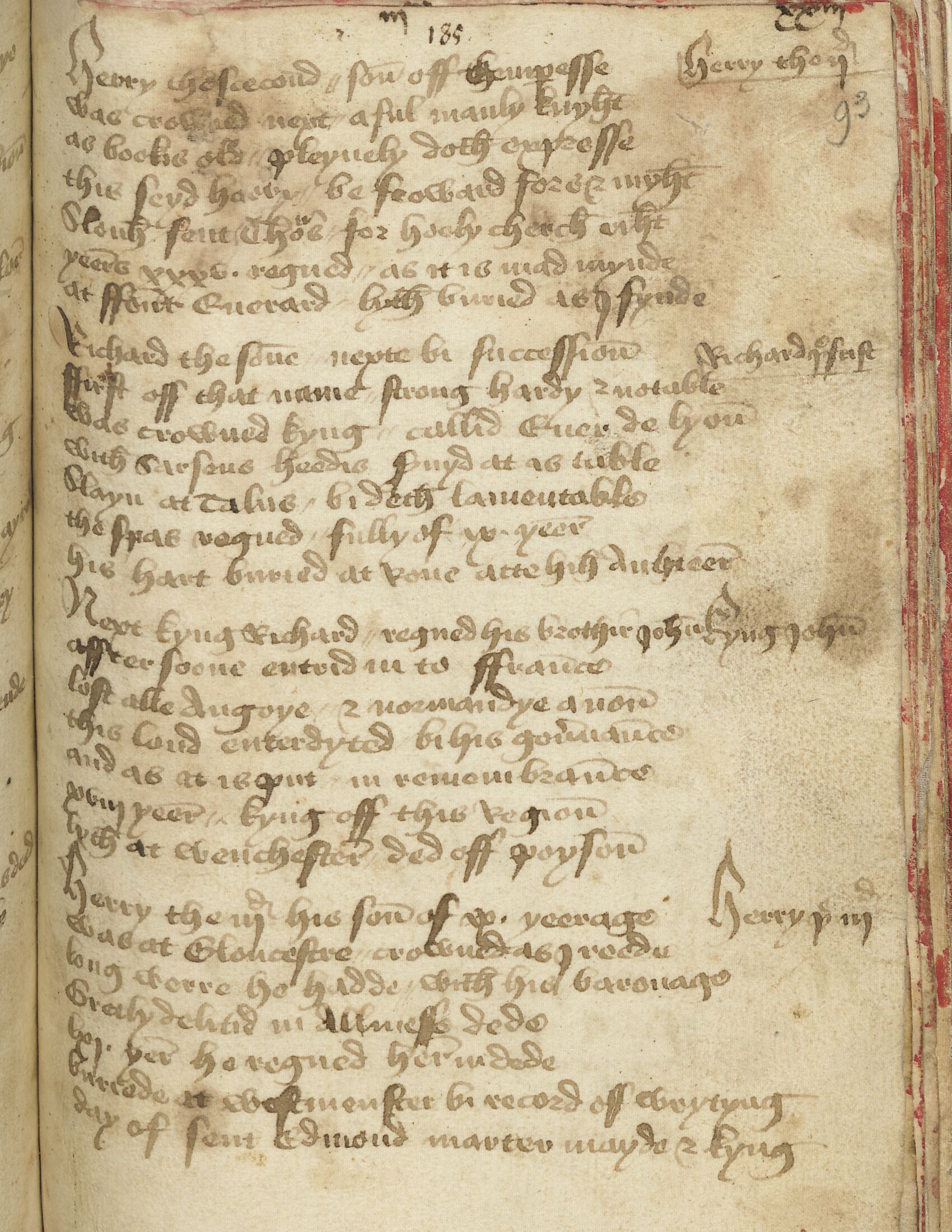

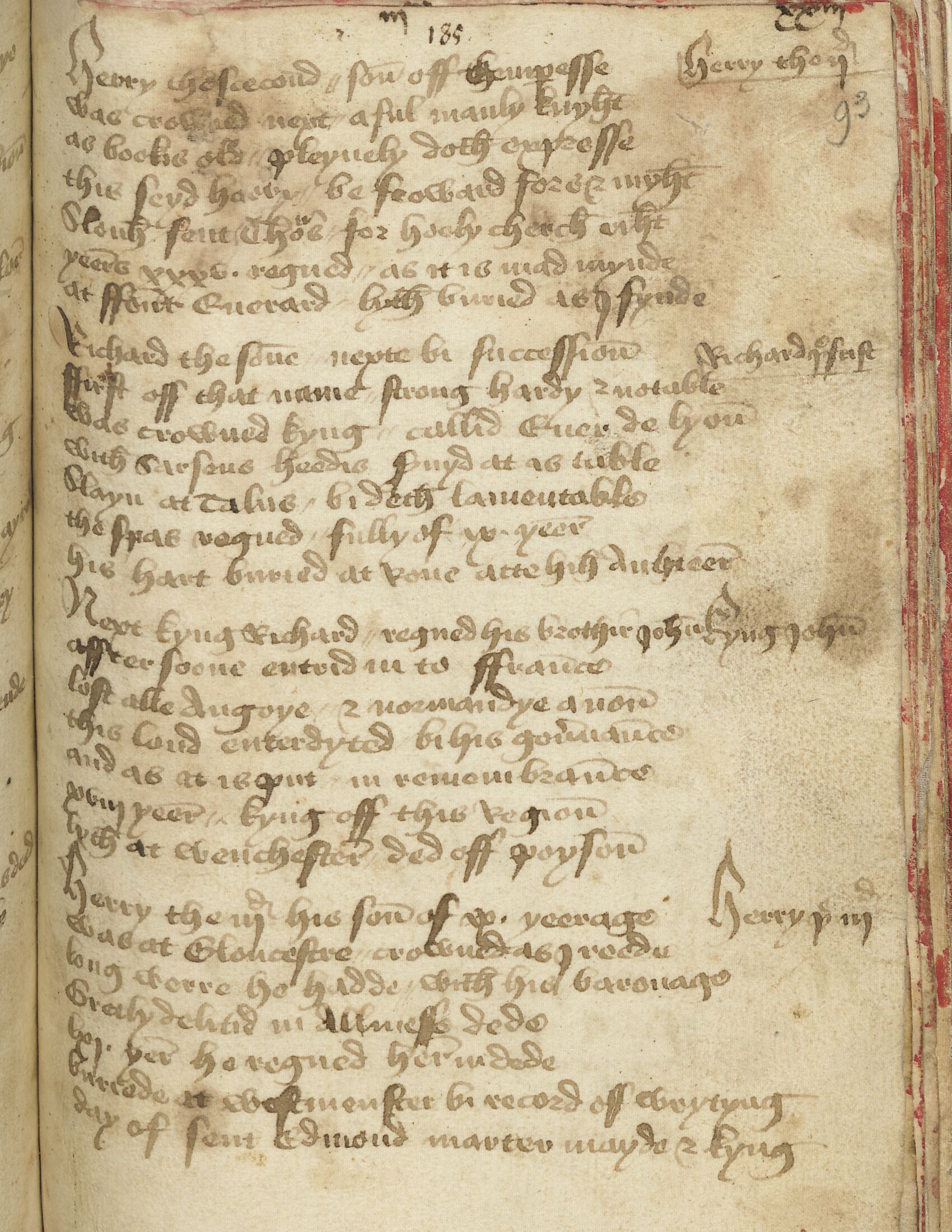

Herry the scecond // son off themp(er)esse Herry the ijd

was crowned next // a ful manly knyht

as bookis old // pleynely doth expresse

this seyd harry // be froward fors (and) myht

Slouh sent Tho(m)as // for hooly cherch riht

yeer(e)s xxxv. regned // as it is mad mynde

at ffont Euerard // lyth buried as I fynde

Richard the son(n)e // nexte bi succession Richard þe frist

ffirst off that name // strong hardy (and) notable

was crowned kyng // callid Cuer de Lyon

with Sarsens heedis s(er)uyd at is table

Slayn at Talus // bi deth lamentable

The spas regned // fully of ix. yeer

his hart buried at Roue atte hih Auhteer

Next kyng Richard // regned his brothir Iohn Kyng John

affter soone entrid in to ffrau(n)ce

lost alle Angoye // (and) normandye anon

this lond enterdyted // bi his gou(er)nau(n)ce

and as it is put // in remembrau(n)ce

xviij yeer // kyng off this Region

lyth at wenchester //ded off poyson

Herry the iijd his son of ix. yeerage Herry þe iijd

was at Gloucestre // crowned as I reede

long werre he hadde // with his baronage

Gretly delitid in Allmesse dede

lxj. yer he regned her indede

buriede at westmenster bi record off wrytyng

day of sent Edmond marter mayde (and) kyng

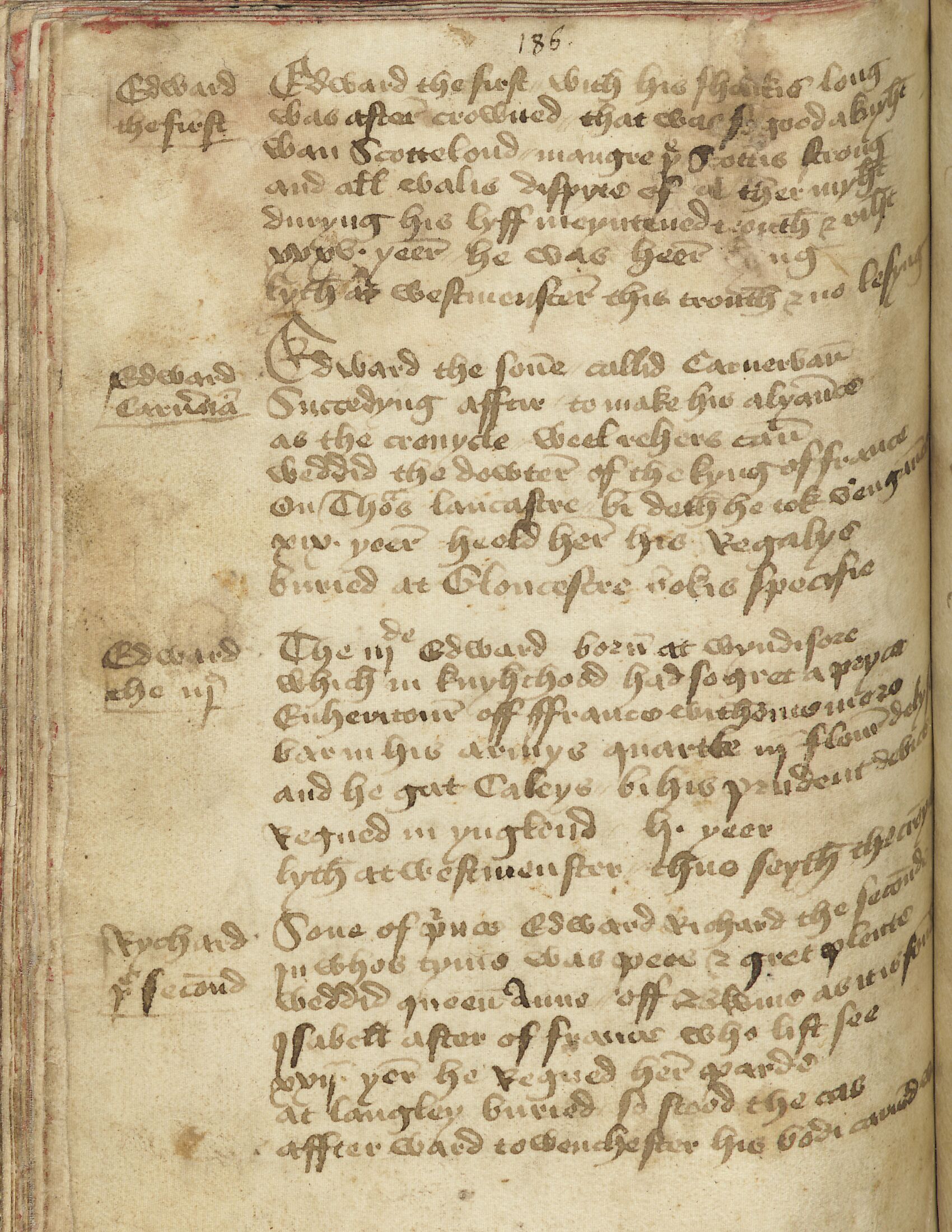

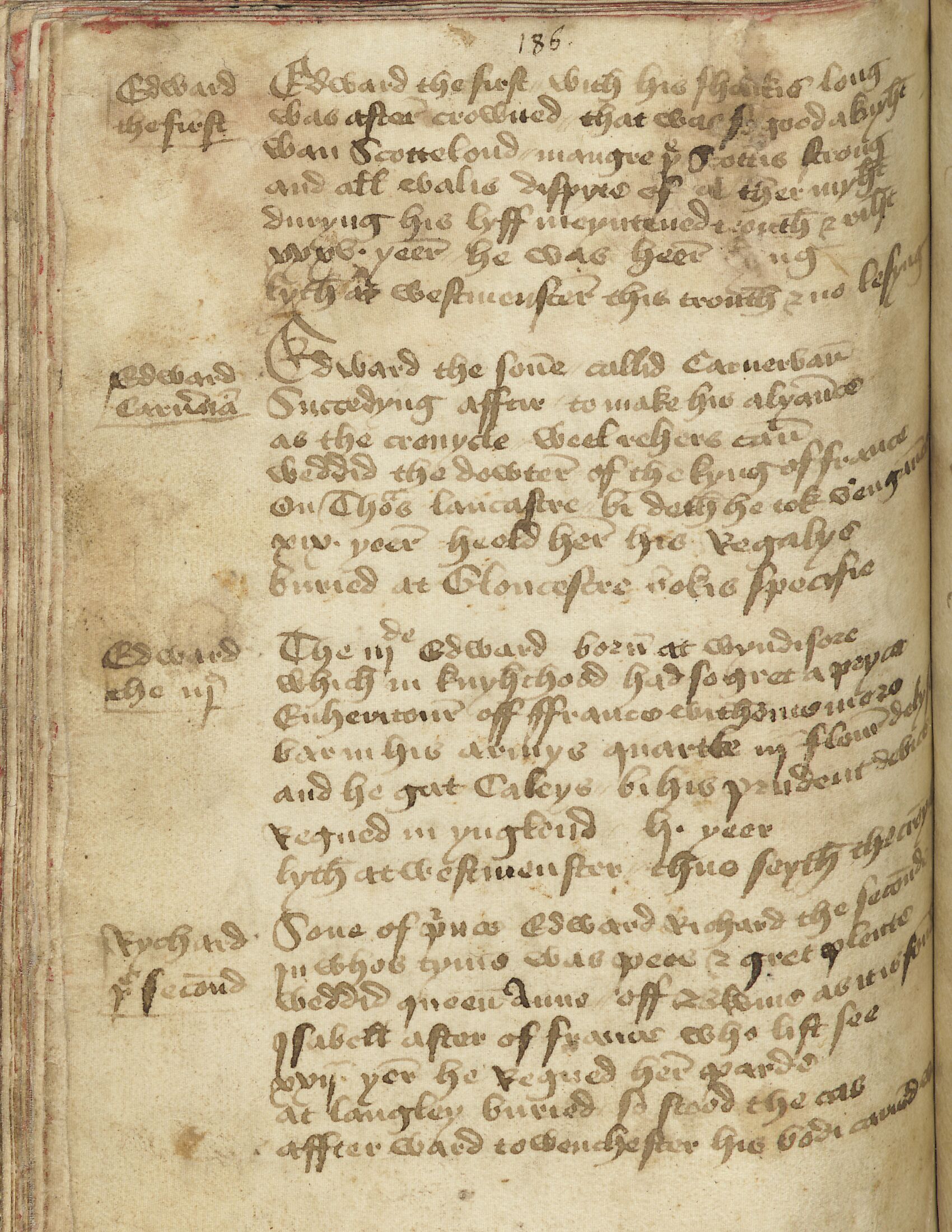

Edward Edward the first // with his shankis long

the first was after crowned // that wa[[s]] s[[o]] good a knyht

wan Scottelond // in angre þe Scottis krong

and all walis dispyte of al ther myht

duryng his lyff meyntened t[[r]]outh (and) riht

xxxv. yeer // he was heer [[ky]]ng

lyth at westmenster this trouth (and) no lesyng

Edward Edward the son(n)e // callid Carnervan

Carn(er)ua(n) Succedyng afftir // to make his alyau(n)ce

as the cronycle // weel rehers can

weddid the dowter of the kyng of france

On Tho(m)as lancastre // bi deth he tok vengau(n)ce

xix. yeer heold her his Regalys

buried at Gloucestre bokis specifie

Edward The iijde Edward born at wyndisore

the iijd which in knyhthood had so gret a pryce

Enheritour off ffrance withoute more

bar in his armys quartke iij flour delys

and he gat Caleys // bi his prudent device

Regned in ynglond // lj. yeer

lyth at westmenster // thus seyth the cro(n)y†cle†

Rychard Sone of p(ri)nce Edward Richard the secou(n)d

þe secou(n)d in whos tyme was pees (and) gret plente

weddid queen Anne // off Bwme as it is found

Isabell after of france who list see

xxij. yer he Regned her parde

at langley buried so stood the cas

affter ward to wenchester his bodi caried †was†

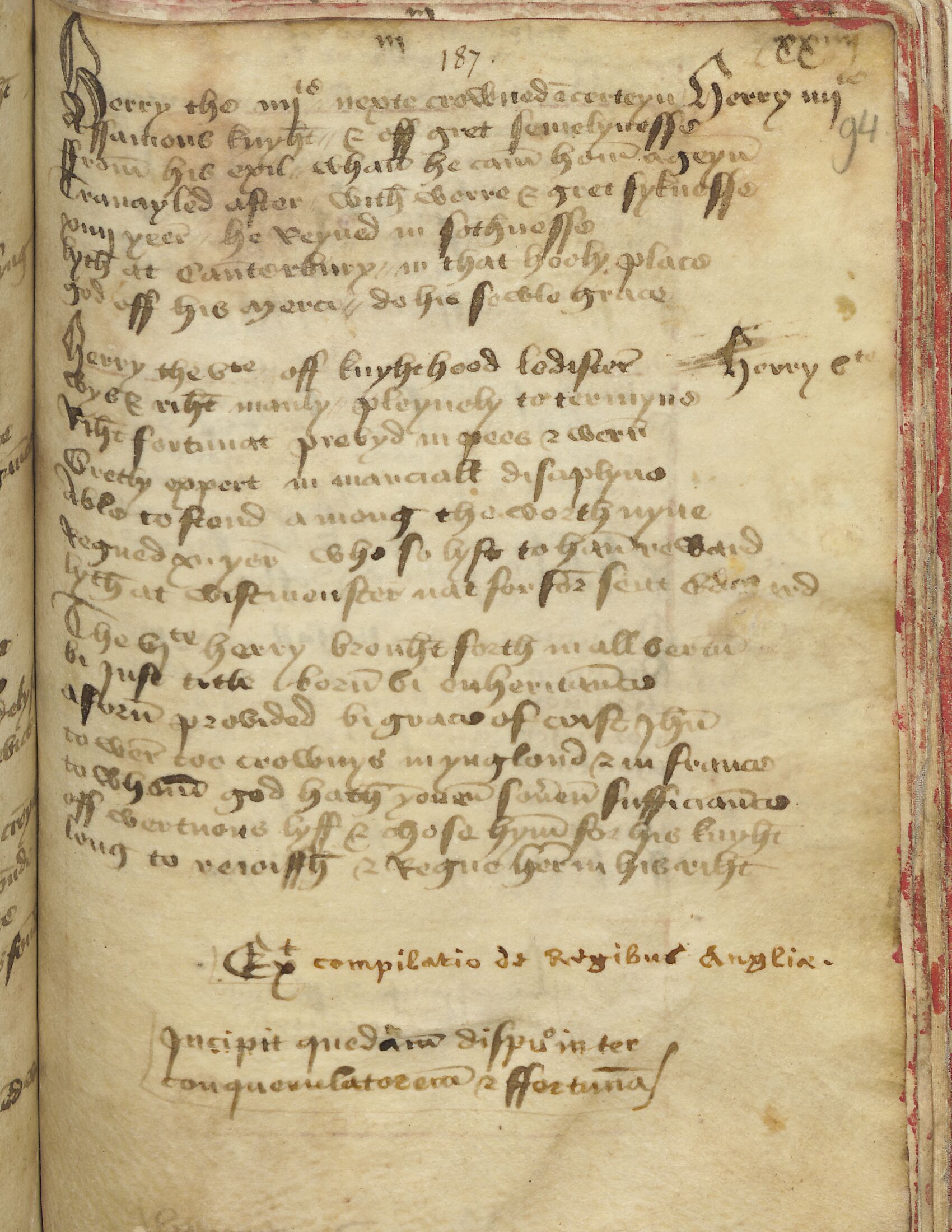

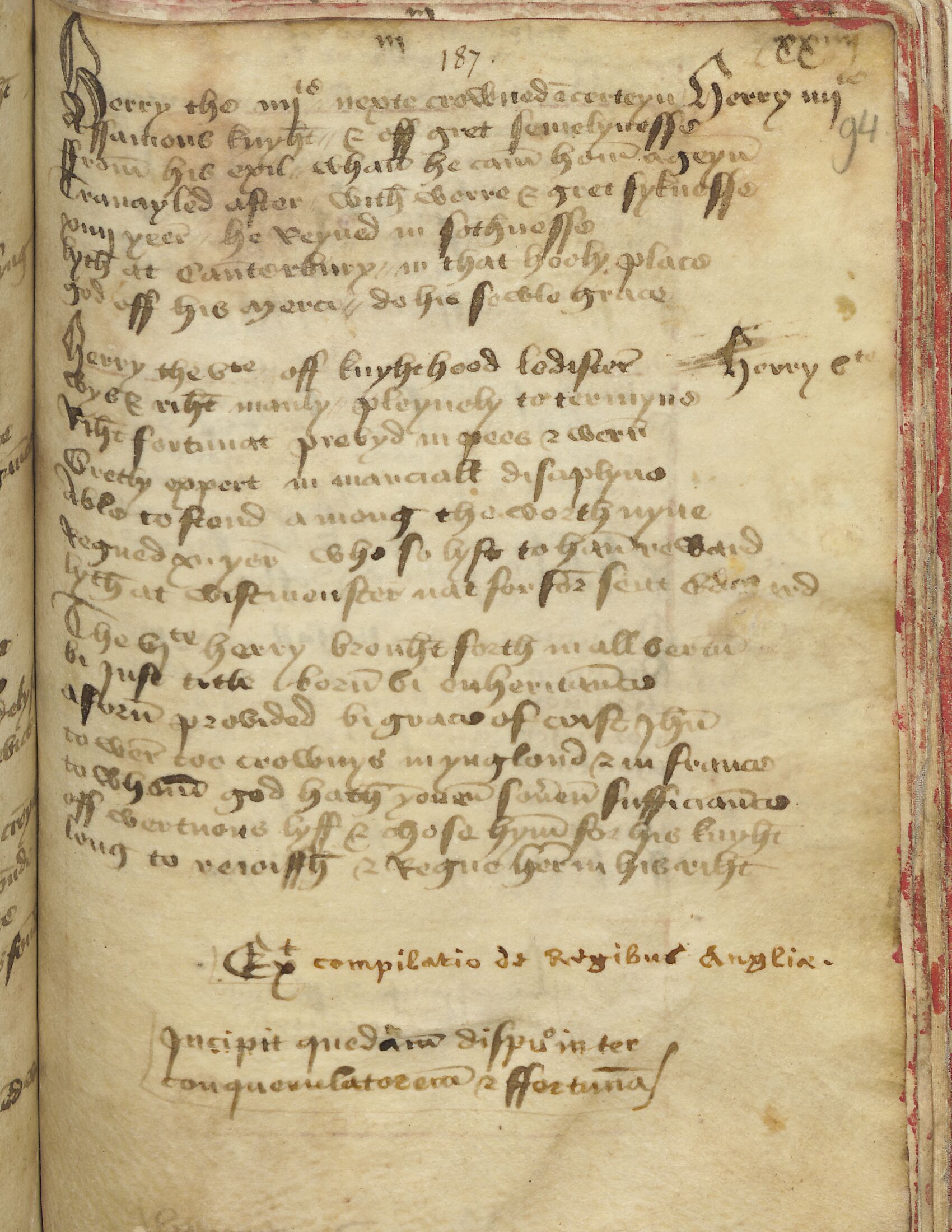

Herry the iiiite // nexte crowned a(n) certeyn [margin: Herry the iiiite]

A ffamous knyht // (and) off gret semelynesse

ffrom his exil // whan he cam hom ageyn

Trauayled after // with werre (and) gret syknesse

xiiij yeer // he reyned in sothnesse

lyth at Cau(n)terbury // in that hooly place

god off his merci // do his sowle grace

Herry the vte / off knyhthood lodister [margin: Herry the vte]

Wys (and) riht manly/ pleynely to termyne

Riht fortunat prevyd in pees (and) werr

Gretly expert in marciall disciplyne

Able to stond a mong the worth nyne

Regned xii yer who so lyst to han reward

lyth at wistmenster nat far for(m) sent Edward

The vite herry brouht forth in all vertu

bi just title born bi enheritance

aforn provided bi grace of crist jh(es)u

to wer too crownys in ynglond (and) in france

to whom god hath yeuen sou(er)en sufficiau(n)ce

off wertuous lyff (and) chose hym for his knyht

long to reioissh & Regne her in his riht

Ex(plici)t compilatio de Regibus Angliæ

Introduction to MS Leiden Lydgate ff. 92v-94r: The Kings of England sithen William Conquerour, or John Lydgate, Verses on the Kings of England (to Henry VI)

A. Content and form

A1. Content

This poem consists of fifteen brief poetic stanzas about the kings of England, from William the Conqueror to Henry VI, thus portraying the English monarchy from the eleventh to the fifteenth century. The stanzas describe the kings’ heritage (name and previous king), their deeds − both good and bad, how many years they ruled, their death, and their burial place. For example, in the stanza about William Rufus on f. 92v, line one and two: “Nexte in ordre // bi succession / will(i)am Rufus his sone crowned kyng” concern his heritage. Line three to five tell about his deeds, here negative ones: “which to godward had no devocion / distroyed cherchis // off new (and) olde beldyng / to make a forest // plesant for hu(n)tyng”. The last two lines state the number of years he ruled, “xiiij yer // bar his crowne in deede,” and his burial place, “buryed at wenchester // the crownycle ye may †rede†”.

A2. Themes

Not surprisingly, the main theme of the poem is the English monarchy. In general, it is a praise of kings. The more recent the king is to Lydgate, the more positive the description seems to be. Perhaps the author felt that critiquing older kings was less dangerous. One of the themes present in this poem is the War of the Roses (1455 − 1485), the dispute between the House of Lancaster and the House of York about who possessed the rightful claim on the English throne. Lydgate had strong ties to the Lancastrian kings Henry V and VI, as these were his patrons, and this is also evident in his description of these kings in the poem. In the poem, Henry VI’s description states: “henry the vi: bi iust title, bi grace of crist jhesus, regne her in his riht” (f. 94r). Thus, according to Lydgate, he is indeed the rightful king. All Lancastrians are depicted as good kings, which also shows Lydgate’s loyalties. Another source of turbulence during the reigns of the last few kings in the poem is the Hundred Years’ War (1337 −1453), a conflict between the English and French monarch over the rule of France. This can also be traced back in the poem. For example, Edward III is said to be “Enheritour off ffrance” and “gat Caleys // bi his prudent device” (f. 93v). Henry IV and Henry V are both reported to have reigned “with werre (and) gret syknesse” and “in pees (and) werr” respectively (f. 94r). Lydgate thus strongly supports the English claim in this conflict. The conflict with France might also have infused a sense of nationalism with regard to the English kings, even though nationalism saw dips during this period. The kings that were involved in the Hundred Years’ War are mostly described positively. For example Henry IV is described as “A ffamous knyht,” while Henry V is depicted as “Able to stond a mong the worth nyne” (f. 94r). However, Lydgate does not seem to have a particular opinion about French-Norman kings, who are judged on their actions instead of their nationality, such as in William Rufus’ case.

A3. Genre

This poem can be identified as a chronicle, which provides simple summaries of historical events in chronological order. Historical writing was not unknown to medieval literature. Some examples of other historical writing are Geoffrey Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae (1136) and Layamon’s Brut (1190 − 1215). In the later Middle Ages, “a new type of vernacular chronicle gained prominence: the verse chronicle.” Lydgate’s poem could be said to be part of this new type. These verses “focused more on detail, elaborate descriptions, and the development of individual styles.” However, different from these works, this short poem contains only rudimentary information on the kings. The stanzas are just seven lines (in contrast: Brut has 16,095 lines in total) of enumerating facts about kings, with only their major deeds being mentioned.

A4. Formal aspects

The poem contains seven lines per stanza and fifteen stanzas, thus 105 lines in total. It is written in rhyme royal, which was introduced to English poetry by Geoffrey Chaucer. This entails decasyllabic verse lines, with a rhyme scheme of a-b-a-b-b-c-c. One of the scribe’s characteristics is to place two slashes halfway lines. In general, the scribe uses double slashes either in between five syllables on each side or with four syllables before and six syllables after. Thus, the slashes indicate a caesura. This can be linked to the influence of French poetry, which also used caesuras, on Lydgate. For example, French alexandrine poetry has twelve syllables in a line with a caesura in the middle, creating two half-lines of six syllables. Throughout the poem, the metre often does not seem fully consistent, based on spelling, but could be regularised with alternative pronunciations, as the result of elision, synizesis, apocope and syncope. However, sometimes the poem appears to have some irregularities which are not easily resolved through the postulation of these phonetic processes. For example, the line “at langley buried so stood the cas” (f. 93v) seems to have only nine spelled syllables, while “On Tho(m)as lancastre // bi deth he tok vengau(n)ce” (f. 93v) appears to have thirteen spelled syllables. If these are indeed cases of irregularity, it seems more likely that these are the result of copying errors on the part of the scribes. Although sometimes the metre is a little irregular, it is a useful aid in deducing pronunciation of particular words − providing examples here from the first stanza of f. 92v. For instance, the French city Caen is spelled as “Cane”, but through the metre it is clear that the pronunciation with regard to syllables is likely to be similar how it would be nowadays, namely /kan/ rather than /´ka -nə/. Furthermore, the i in both “mencion” and “possession” is pronounced as a separate syllable /i/. The same goes for final -e’s, which sometimes seem to be pronounced according to the metre, such as in: “As bokis oldë // makë mencion”. The rhyme scheme, too, is useful to deduce which words were meant to rhyme. Through the rhyme scheme, for example, it may be argued that “cronyclar” should perhaps be cronycleer as it rhymes with “yeer”.

B. Cultural and Literary Context

B1. Date and origin

The text’s origin most probably lies in England, because of the English nationalistic character of the poem, its Middle English language, and the manuscript witnesses’ origins in England. If the poem was indeed written by Lydgate, it may have been composed in Bury St Edmunds, the abbey where he spent most of his life, or in Essex, where he lived between 1421 and 1431, depending on the exact date of the poem. The poem was definitely written after Henry VI became king of England in 1421 and of France in 1422. The text does not mention his death in 1471 or his deposition from the throne in 1461. Lydgate died around 1451, so if he wrote it, it would be between 1421 and 1451. The scholar Mooney dates the earliest exactly datable extant manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 686) containing this poem to 1429-1430 from internal evidence in the rest of the manuscript. Therefore it is likely that the poem was written between 1422 and 1429.

B2. Author & implied/intended audience

The author is said to be John Lydgate in all modern scholarship. There is no intended audience found in the text, but it could be meant for everyone learning history in an informal setting. According to Mooney, the poem was to be read out loud, perhaps to children learning history and/or grammar. The poem also has a political purpose, to glorify the monarchy of England − in case of Lydgate, his royal patron. The DIMEV supports this by stating that the poem is written for Lydgate’s patron King Henry VI.

B3. Overview of scholarship

Although the text seems to have been very popular given its wide dissemination, not much has been written about this text in modern scholarship. This might be due to the fact that Lydgate is a less popular author nowadays. Linne Mooney discusses this text alongside another anonymous verse about kings to study how this text relates to its political context and its continued use as a form of political propaganda. Mooney has written another article on this text, together with Adrian C. Barbrook, Christopher J. Howe and Matthew Spencer. They have conducted a stemmatic analysis of the text in all manuscript and print witnesses, using both manual and digital techniques. MS Leiden is categorised in a group with eight others, mostly manuscripts from the fifteenth century, which share common variants. Leiden’s poem is closely connected to Lansdowne 699, which Van Dorsten already indicated for another text of Lydgate in the Leiden MS. C. F. Bühler discusses the date of the same poem in MS Ashmole 59, which has the name of Edward IV added at the end of the poem. He compares this particular manuscript to an earlier version of the text, namely in Dublin Trinity College MS 516, which does not contain the additional stanza. This article contains an elaborate enumeration of variation between the two manuscripts. Bühler however does not seem to be overly fond of the poem, as he describes it as “fifteen practically worthless stanzas”. Van Dorsten only names the poem “The Kings of England Sithen William Conquerour” without mentioning additional information, not even an author. He does however sketch the Leiden manuscript context for the poem. Further information on Lydgate can be found in James Simpson’s article, who discusses Lydgate’s characteristics as an author and advocates further scholarly research on his texts.

C. Language

Orthography/Spelling: There are some noteworthy characteristics with regard to spelling in this poem. For example, there is an occasional use of the thorn character (þ), which is rather archaic. One example is “þe Scottis krong” (f. 93v). Other occurrences are found in the margins. Furthermore, the scribe of this poem has a particular tendency to use double ff’s, even though the letter is not meant as a capital F. Particularly interesting in relation to spelling are names of kings and place names. For example, throughout the poem, the name Henry is spelled as “herry”. Some place names are also spelled differently than one would expect, such as the mysterious “Bwme,” likely to refer to Bohemia and “Angoye,” for modern day Anjou (f. 93v, f. 93r). Finally, another special phenomenon occurs in “thempresse” and “therchebisshop” (f. 92v, f. 93r). Both these instances are contracted forms as a result of elision. The vowel of the determiner “the” is absorbed by the initial vowel of empresse and erchebisshop respectively. It is likely that this spelling is the result of fitting in with the metre.

Morphology: As regards morphology, the poem does not seem to reveal any unusual characteristics. The personal pronouns appear to have no irregularities. Furthermore, the poem uses -th endings in third person singular contexts: “to whom god hath yeuen sou(er)en sufficiau(n)ce” (f. 94r). Thus, the poem does not resemble a Northern dialect with -s endings. Finally, during the Middle English period, the -e endings slowly began to disappear in spoken form, but sometimes remained in spelling variants. Throughout the poem, nouns, adjectives, and past-tense verbs sometimes have a final -e. It is debatable whether these were pronounced, as there are some instances whereby the final -e is needed to get the correct number of syllables in the line. Three such examples are “bookis oldë”, “regnedë” and “burydë” (f. 92v).

Syntax: One particular characteristic of the poem’s style relates to syntax. In this poem, the stanzas consist of a summation of facts about kings. The style of the language clearly resembles this. The particular way in which the individual facts are enumerated may be characterised by the term asyndeton, a series of related clauses that lack coordinating conjunctions, such as and. For example, in the first stanza, the audience is informed that William the Conqueror “mad kyng [...] put out herald // tooke possession / bar his crowne [...] buried at Cane” (f. 92v). The five different phrases here are not coordinated. Further adding to the style of this poem as a enumeration of facts, is the way in which tensed verbs occasionally lack a direct grammatical subject. For example, in the tensed verbs in the first stanza as quoted above have no direct grammatical subject like he. They all still retrospectively refer to William. Occasionally in the poem, a personal pronoun he is used, but often no grammatical subject is given. Additionally, in some cases passive constructions using a past participle lack a tensed auxiliary. This happens twice in the first stanza: “mad kyng” and “buried at Cane” (f. 92v). Both these instances lack a form like was. Finally, the poem also sometimes shows an unusual word order. One example is “affter ward to wenchester his bodi caried †was†” (f. 93v). It is possible that this word order is there to fit in with the metre of the poem and to have “was” rhyme with “cas” (f. 93v).

Vocabulary: The poem occasionally uses French loanwords. For instance “alyaunce” and “enheritour” are both originally French words (f. 93v). The use of French words is not surprising, given the great influence of French on the English language, but, still, the use of French loanwords shows the aureate style of the poet. Furthermore, the rich style that was associated with French loanwords also fits the subject matter, as this poem celebrates the rule of kings.

Dialect: From the spelling of certain words, some suggestions may be made as to the dialect this poem represents. First of all, the -th ending in makith and seyth clearly indicate that this text is not a Northern text, but a Southern one. Words with a velar fricative /x/ such as knyht, myht, riht are all spelled with h rather than gh, which, according to Horobin, points to a Suffolk dialect and Lydgate’s own particular use. Furthermore, the spelling of ageyn and nat reveal influences of Samuel’s type III (Chaucerian) standard. Based on the eLALME data, the usage of ageyn, nat, buryede, buryed, callid, and heold individually all suggest a Southern dialect rather than a Northern one. However, other spelling features, like hooly, seyth, and sorwe individually seem point north of London at least. It might, of course, be the case that these features result from the work of different scribes. Together, these features combined in eLALME give seven locations whose linguistic profiles strongly correspond to that of this text. One of these is located on the border between Suffolk and Norfolk, where ageyn, nat and sorwe are frequently attested. Two other locations also lie in counties adjacent to Suffolk, where these same words are used, though less frequently, while one is located just west of Norfolk, where nat and sorwe are frequently attested, with seyth only occasionally indicated. The other three locations are scattered throughout the country, but all in the South. Thus, based on eLALME and these features, the text might resemble an Eastern dialect. This ties in with Lydgate’s own Suffolk origin, but also with the name of one of the manuscript’s first owners, John Kyng of Dummowe, as Dunmow lies in Essex.

D. Transmission of text

D1. Transmission

The text survives in 36 manuscripts, thus, as Mooney points out, suggesting its popularity at the time. The oldest manuscript is Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 686 (c. 1430 − 1440). Of the 36 extant manuscripts, 32 are from the fifteenth century, three from the sixteenth century and one from the seventeenth century. Additionally, there are three print versions of the text. This shows the text’s prolonged popularity and use.D2. Witness-specific information

There are many different versions of this poem in the extant manuscripts. Several manuscripts other than Leiden contain additional stanzas, added to either the beginning or the end, concerning other kings, for example the reigns between Alfred the Great and Harold Godwinson, or the subsequent reigns after 1461. These stanzas are not written by Lydgate, but do show the continued use of the poem for political ends.

D3. Scribe

Scribe I of Leiden wrote this text. This scribe is English, from the second half of the fifteenth century, who writes in a cursive hand. He was responsible for most of the texts in this manuscript, including Lydgate’s Fall of Princes − another royally-themed poem.

D4. How was it read/used?

Study has found no notes added to the poem in Leiden. However, there are a few reading aids provided, such as the Latin title at the top, which has been added to the manuscript by the Dutch scholar Franciscus Junius, a sixteenth/seventeenth-century owner. Furthermore, the kings’ names in the margin serve as helpful aids that indicate which king is dealt with in the stanza. These names seem to be the same handwriting as the main text, but they could have been added later as well. These additions would clarify the text more and serve a learners audience.

E. Bibliographical overview:

E1. Bibliography secondary scholarship

Benskin, M., M. Laing, V. Karaiskos and K. Williamson. An Electronic Version of A

Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh,

2013. http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ihd/elalme/elalme.html

Britannica Academia. “Alexandrine.” Accessed December 14, 2017, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/alexandrne/5637 (direct link) or

https://login.leidenuniv.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/alexandrne/5637 (via Leiden proxy)

Bühler, C.F. “Lydgate’s Verses on the Kings of England.” Review of English Studies 9, no.

47 (1933): 47-50. ProQuest. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1293805918?accountid=12045 (direct link) or

https://login.leidenuniv.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1293805918?accountid=12045 (via Leiden proxy)

Gale Encyclopedia of World History: War. Encyclopedia.com. “The Hundred Years’ War

(1337–1453).” Accessed December 14, 2017.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hundred-years-war-1337-1453

Horobin, Simon. The Language of the Chaucer Tradition. New York: D.S. Brewer, 2003.

Lambdin, Laura C., and Robert T. Lambdin. A Companion to Old and Middle English

Literature. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. eBook Collection

(EBSCOhost).

Mooney, Linne R. “Lydgate's ‘Kings of England’ and Another Verse Chronicle of the

Kings.” Viator 20 (1989): 255-289. ProQuest.

Mooney, Linne R., Adrian C. Barbrook, Christopher J. Howe and Matthew Spencer.

“Stemmatic Analysis of John Lydgate’s Verse Chronicle, ‘The Kings of England

Sithen William the Conqueror’.” Revue d'Histoire des Textes vol. 31 (2003): 277-299.

Mooney, Linne R., Daniel W. Mosser, Elizabeth Solopova, Deborah Thorpe, Daniel Hill

Radcliffe, eds. The Digital Index of Middle English Verse. http://www.dimev.net/

Samuels, M.L. “Some applications of Middle English dialectology.” English Studies 44

(1963): 81-94.

Simpson, James. “John Lydgate.” In A Cambridge Companion to Medieval English

Literature 1100-1500, edited by Larry Scanlon, 205-216. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009.

Van Dorsten, J.A. “The Leiden ‘Lydgate’ Manuscript.” Scriptorium 12 (1960): 315-325.

E2: Link to text in Digital Index of Medieval English Verse

http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=5731#wit-5731-36

ff. 92v-94r: The Kings of England sithen William Conquerour

Compilatio quæda(m) de Regibus Angliæ

will(i)am con querour His mythy will(i)am // duk off Normandye

As bokis olde // make mencion

By iust title // (and) bi his chyualrye

mad kyng be conqueste // off Brutis Albion

put out herald // tooke possession

bar his crowne // ful oon (and) twenty yeer

Buried at Cane // thus seyth the cronyclar

[[wi]]ll(i)am Rufus Nexte in ordre // bi succession

will(i)am Rufus his sone crowned kyng

which to godward had no devocion

distroyed cherchis // off new (and) olde beldyng

to make a forest // plesant for hu(n)tyng

xiiij yer // bar his crowne in deede

buryed at wenchester // the crownycle ye may †rede†

Herry the His brothir nexte // called the ffrist herry

ffriste was at london crowned as I fynd

whos brothir Robert // duk of normandye

gan hym werreye // the cronycle makith mende

Reconsiled all rancour seet be hynde

fful xxxj yeer // bi recorde off wrytyng

he regnede // buryede at redyng

Steph(e)n His Cosyn Steph(e)n // whan frist herry was ded

towarde ynglond // gan to crosse his saylle

therchebisshop seet vpon his heede

a Rych crowne // beyng off his conselle

xix yer // with sorwe (and) gret travaille

he bar his crowne // had neu(er) rest

at ffeuersham lith buried in a chest

Herry the scecond // son off themp(er)esse Herry the ijd

was crowned next // a ful manly knyht

as bookis old // pleynely doth expresse

this seyd harry // be froward fors (and) myht

Slouh sent Tho(m)as // for hooly cherch riht

yeer(e)s xxxv. regned // as it is mad mynde

at ffont Euerard // lyth buried as I fynde

Richard the son(n)e // nexte bi succession Richard þe frist

ffirst off that name // strong hardy (and) notable

was crowned kyng // callid Cuer de Lyon

with Sarsens heedis s(er)uyd at is table

Slayn at Talus // bi deth lamentable

The spas regned // fully of ix. yeer

his hart buried at Roue atte hih Auhteer

Next kyng Richard // regned his brothir Iohn Kyng John

affter soone entrid in to ffrau(n)ce

lost alle Angoye // (and) normandye anon

this lond enterdyted // bi his gou(er)nau(n)ce

and as it is put // in remembrau(n)ce

xviij yeer // kyng off this Region

lyth at wenchester //ded off poyson

Herry the iijd his son of ix. yeerage Herry þe iijd

was at Gloucestre // crowned as I reede

long werre he hadde // with his baronage

Gretly delitid in Allmesse dede

lxj. yer he regned her indede

buriede at westmenster bi record off wrytyng

day of sent Edmond marter mayde (and) kyng

Edward Edward the first // with his shankis long

the first was after crowned // that wa[[s]] s[[o]] good a knyht

wan Scottelond // in angre þe Scottis krong

and all walis dispyte of al ther myht

duryng his lyff meyntened t[[r]]outh (and) riht

xxxv. yeer // he was heer [[ky]]ng

lyth at westmenster this trouth (and) no lesyng

Edward Edward the son(n)e // callid Carnervan

Carn(er)ua(n) Succedyng afftir // to make his alyau(n)ce

as the cronycle // weel rehers can

weddid the dowter of the kyng of france

On Tho(m)as lancastre // bi deth he tok vengau(n)ce

xix. yeer heold her his Regalys

buried at Gloucestre bokis specifie

Edward The iijde Edward born at wyndisore

the iijd which in knyhthood had so gret a pryce

Enheritour off ffrance withoute more

bar in his armys quartke iij flour delys

and he gat Caleys // bi his prudent device

Regned in ynglond // lj. yeer

lyth at westmenster // thus seyth the cro(n)y†cle†

Rychard Sone of p(ri)nce Edward Richard the secou(n)d

þe secou(n)d in whos tyme was pees (and) gret plente

weddid queen Anne // off Bwme as it is found

Isabell after of france who list see

xxij. yer he Regned her parde

at langley buried so stood the cas

affter ward to wenchester his bodi caried †was†

Herry the iiiite // nexte crowned a(n) certeyn [margin: Herry the iiiite]

A ffamous knyht // (and) off gret semelynesse

ffrom his exil // whan he cam hom ageyn

Trauayled after // with werre (and) gret syknesse

xiiij yeer // he reyned in sothnesse

lyth at Cau(n)terbury // in that hooly place

god off his merci // do his sowle grace

Herry the vte / off knyhthood lodister [margin: Herry the vte]

Wys (and) riht manly/ pleynely to termyne

Riht fortunat prevyd in pees (and) werr

Gretly expert in marciall disciplyne

Able to stond a mong the worth nyne

Regned xii yer who so lyst to han reward

lyth at wistmenster nat far for(m) sent Edward

The vite herry brouht forth in all vertu

bi just title born bi enheritance

aforn provided bi grace of crist jh(es)u

to wer too crownys in ynglond (and) in france

to whom god hath yeuen sou(er)en sufficiau(n)ce

off wertuous lyff (and) chose hym for his knyht

long to reioissh & Regne her in his riht

Ex(plici)t compilatio de Regibus Angliæ

Introduction to MS Leiden Lydgate ff. 92v-94r: The Kings of England sithen William Conquerour, or John Lydgate, Verses on the Kings of England (to Henry VI)

A. Content and form

A1. Content

This poem consists of fifteen brief poetic stanzas about the kings of England, from William the Conqueror to Henry VI, thus portraying the English monarchy from the eleventh to the fifteenth century. The stanzas describe the kings’ heritage (name and previous king), their deeds − both good and bad, how many years they ruled, their death, and their burial place. For example, in the stanza about William Rufus on f. 92v, line one and two: “Nexte in ordre // bi succession / will(i)am Rufus his sone crowned kyng” concern his heritage. Line three to five tell about his deeds, here negative ones: “which to godward had no devocion / distroyed cherchis // off new (and) olde beldyng / to make a forest // plesant for hu(n)tyng”. The last two lines state the number of years he ruled, “xiiij yer // bar his crowne in deede,” and his burial place, “buryed at wenchester // the crownycle ye may †rede†”.

A2. Themes

Not surprisingly, the main theme of the poem is the English monarchy. In general, it is a praise of kings. The more recent the king is to Lydgate, the more positive the description seems to be. Perhaps the author felt that critiquing older kings was less dangerous. One of the themes present in this poem is the War of the Roses (1455 − 1485), the dispute between the House of Lancaster and the House of York about who possessed the rightful claim on the English throne. Lydgate had strong ties to the Lancastrian kings Henry V and VI, as these were his patrons, and this is also evident in his description of these kings in the poem. In the poem, Henry VI’s description states: “henry the vi: bi iust title, bi grace of crist jhesus, regne her in his riht” (f. 94r). Thus, according to Lydgate, he is indeed the rightful king. All Lancastrians are depicted as good kings, which also shows Lydgate’s loyalties. Another source of turbulence during the reigns of the last few kings in the poem is the Hundred Years’ War (1337 −1453), a conflict between the English and French monarch over the rule of France. This can also be traced back in the poem. For example, Edward III is said to be “Enheritour off ffrance” and “gat Caleys // bi his prudent device” (f. 93v). Henry IV and Henry V are both reported to have reigned “with werre (and) gret syknesse” and “in pees (and) werr” respectively (f. 94r). Lydgate thus strongly supports the English claim in this conflict. The conflict with France might also have infused a sense of nationalism with regard to the English kings, even though nationalism saw dips during this period. The kings that were involved in the Hundred Years’ War are mostly described positively. For example Henry IV is described as “A ffamous knyht,” while Henry V is depicted as “Able to stond a mong the worth nyne” (f. 94r). However, Lydgate does not seem to have a particular opinion about French-Norman kings, who are judged on their actions instead of their nationality, such as in William Rufus’ case.

A3. Genre

This poem can be identified as a chronicle, which provides simple summaries of historical events in chronological order. Historical writing was not unknown to medieval literature. Some examples of other historical writing are Geoffrey Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae (1136) and Layamon’s Brut (1190 − 1215). In the later Middle Ages, “a new type of vernacular chronicle gained prominence: the verse chronicle.” Lydgate’s poem could be said to be part of this new type. These verses “focused more on detail, elaborate descriptions, and the development of individual styles.” However, different from these works, this short poem contains only rudimentary information on the kings. The stanzas are just seven lines (in contrast: Brut has 16,095 lines in total) of enumerating facts about kings, with only their major deeds being mentioned.

A4. Formal aspects

The poem contains seven lines per stanza and fifteen stanzas, thus 105 lines in total. It is written in rhyme royal, which was introduced to English poetry by Geoffrey Chaucer. This entails decasyllabic verse lines, with a rhyme scheme of a-b-a-b-b-c-c. One of the scribe’s characteristics is to place two slashes halfway lines. In general, the scribe uses double slashes either in between five syllables on each side or with four syllables before and six syllables after. Thus, the slashes indicate a caesura. This can be linked to the influence of French poetry, which also used caesuras, on Lydgate. For example, French alexandrine poetry has twelve syllables in a line with a caesura in the middle, creating two half-lines of six syllables. Throughout the poem, the metre often does not seem fully consistent, based on spelling, but could be regularised with alternative pronunciations, as the result of elision, synizesis, apocope and syncope. However, sometimes the poem appears to have some irregularities which are not easily resolved through the postulation of these phonetic processes. For example, the line “at langley buried so stood the cas” (f. 93v) seems to have only nine spelled syllables, while “On Tho(m)as lancastre // bi deth he tok vengau(n)ce” (f. 93v) appears to have thirteen spelled syllables. If these are indeed cases of irregularity, it seems more likely that these are the result of copying errors on the part of the scribes. Although sometimes the metre is a little irregular, it is a useful aid in deducing pronunciation of particular words − providing examples here from the first stanza of f. 92v. For instance, the French city Caen is spelled as “Cane”, but through the metre it is clear that the pronunciation with regard to syllables is likely to be similar how it would be nowadays, namely /kan/ rather than /´ka -nə/. Furthermore, the i in both “mencion” and “possession” is pronounced as a separate syllable /i/. The same goes for final -e’s, which sometimes seem to be pronounced according to the metre, such as in: “As bokis oldë // makë mencion”. The rhyme scheme, too, is useful to deduce which words were meant to rhyme. Through the rhyme scheme, for example, it may be argued that “cronyclar” should perhaps be cronycleer as it rhymes with “yeer”.

B. Cultural and Literary Context

B1. Date and origin

The text’s origin most probably lies in England, because of the English nationalistic character of the poem, its Middle English language, and the manuscript witnesses’ origins in England. If the poem was indeed written by Lydgate, it may have been composed in Bury St Edmunds, the abbey where he spent most of his life, or in Essex, where he lived between 1421 and 1431, depending on the exact date of the poem. The poem was definitely written after Henry VI became king of England in 1421 and of France in 1422. The text does not mention his death in 1471 or his deposition from the throne in 1461. Lydgate died around 1451, so if he wrote it, it would be between 1421 and 1451. The scholar Mooney dates the earliest exactly datable extant manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 686) containing this poem to 1429-1430 from internal evidence in the rest of the manuscript. Therefore it is likely that the poem was written between 1422 and 1429.

B2. Author & implied/intended audience

The author is said to be John Lydgate in all modern scholarship. There is no intended audience found in the text, but it could be meant for everyone learning history in an informal setting. According to Mooney, the poem was to be read out loud, perhaps to children learning history and/or grammar. The poem also has a political purpose, to glorify the monarchy of England − in case of Lydgate, his royal patron. The DIMEV supports this by stating that the poem is written for Lydgate’s patron King Henry VI.

B3. Overview of scholarship

Although the text seems to have been very popular given its wide dissemination, not much has been written about this text in modern scholarship. This might be due to the fact that Lydgate is a less popular author nowadays. Linne Mooney discusses this text alongside another anonymous verse about kings to study how this text relates to its political context and its continued use as a form of political propaganda. Mooney has written another article on this text, together with Adrian C. Barbrook, Christopher J. Howe and Matthew Spencer. They have conducted a stemmatic analysis of the text in all manuscript and print witnesses, using both manual and digital techniques. MS Leiden is categorised in a group with eight others, mostly manuscripts from the fifteenth century, which share common variants. Leiden’s poem is closely connected to Lansdowne 699, which Van Dorsten already indicated for another text of Lydgate in the Leiden MS. C. F. Bühler discusses the date of the same poem in MS Ashmole 59, which has the name of Edward IV added at the end of the poem. He compares this particular manuscript to an earlier version of the text, namely in Dublin Trinity College MS 516, which does not contain the additional stanza. This article contains an elaborate enumeration of variation between the two manuscripts. Bühler however does not seem to be overly fond of the poem, as he describes it as “fifteen practically worthless stanzas”. Van Dorsten only names the poem “The Kings of England Sithen William Conquerour” without mentioning additional information, not even an author. He does however sketch the Leiden manuscript context for the poem. Further information on Lydgate can be found in James Simpson’s article, who discusses Lydgate’s characteristics as an author and advocates further scholarly research on his texts.

C. Language

Orthography/Spelling: There are some noteworthy characteristics with regard to spelling in this poem. For example, there is an occasional use of the thorn character (þ), which is rather archaic. One example is “þe Scottis krong” (f. 93v). Other occurrences are found in the margins. Furthermore, the scribe of this poem has a particular tendency to use double ff’s, even though the letter is not meant as a capital F. Particularly interesting in relation to spelling are names of kings and place names. For example, throughout the poem, the name Henry is spelled as “herry”. Some place names are also spelled differently than one would expect, such as the mysterious “Bwme,” likely to refer to Bohemia and “Angoye,” for modern day Anjou (f. 93v, f. 93r). Finally, another special phenomenon occurs in “thempresse” and “therchebisshop” (f. 92v, f. 93r). Both these instances are contracted forms as a result of elision. The vowel of the determiner “the” is absorbed by the initial vowel of empresse and erchebisshop respectively. It is likely that this spelling is the result of fitting in with the metre.

Morphology: As regards morphology, the poem does not seem to reveal any unusual characteristics. The personal pronouns appear to have no irregularities. Furthermore, the poem uses -th endings in third person singular contexts: “to whom god hath yeuen sou(er)en sufficiau(n)ce” (f. 94r). Thus, the poem does not resemble a Northern dialect with -s endings. Finally, during the Middle English period, the -e endings slowly began to disappear in spoken form, but sometimes remained in spelling variants. Throughout the poem, nouns, adjectives, and past-tense verbs sometimes have a final -e. It is debatable whether these were pronounced, as there are some instances whereby the final -e is needed to get the correct number of syllables in the line. Three such examples are “bookis oldë”, “regnedë” and “burydë” (f. 92v).

Syntax: One particular characteristic of the poem’s style relates to syntax. In this poem, the stanzas consist of a summation of facts about kings. The style of the language clearly resembles this. The particular way in which the individual facts are enumerated may be characterised by the term asyndeton, a series of related clauses that lack coordinating conjunctions, such as and. For example, in the first stanza, the audience is informed that William the Conqueror “mad kyng [...] put out herald // tooke possession / bar his crowne [...] buried at Cane” (f. 92v). The five different phrases here are not coordinated. Further adding to the style of this poem as a enumeration of facts, is the way in which tensed verbs occasionally lack a direct grammatical subject. For example, in the tensed verbs in the first stanza as quoted above have no direct grammatical subject like he. They all still retrospectively refer to William. Occasionally in the poem, a personal pronoun he is used, but often no grammatical subject is given. Additionally, in some cases passive constructions using a past participle lack a tensed auxiliary. This happens twice in the first stanza: “mad kyng” and “buried at Cane” (f. 92v). Both these instances lack a form like was. Finally, the poem also sometimes shows an unusual word order. One example is “affter ward to wenchester his bodi caried †was†” (f. 93v). It is possible that this word order is there to fit in with the metre of the poem and to have “was” rhyme with “cas” (f. 93v).

Vocabulary: The poem occasionally uses French loanwords. For instance “alyaunce” and “enheritour” are both originally French words (f. 93v). The use of French words is not surprising, given the great influence of French on the English language, but, still, the use of French loanwords shows the aureate style of the poet. Furthermore, the rich style that was associated with French loanwords also fits the subject matter, as this poem celebrates the rule of kings.

Dialect: From the spelling of certain words, some suggestions may be made as to the dialect this poem represents. First of all, the -th ending in makith and seyth clearly indicate that this text is not a Northern text, but a Southern one. Words with a velar fricative /x/ such as knyht, myht, riht are all spelled with h rather than gh, which, according to Horobin, points to a Suffolk dialect and Lydgate’s own particular use. Furthermore, the spelling of ageyn and nat reveal influences of Samuel’s type III (Chaucerian) standard. Based on the eLALME data, the usage of ageyn, nat, buryede, buryed, callid, and heold individually all suggest a Southern dialect rather than a Northern one. However, other spelling features, like hooly, seyth, and sorwe individually seem point north of London at least. It might, of course, be the case that these features result from the work of different scribes. Together, these features combined in eLALME give seven locations whose linguistic profiles strongly correspond to that of this text. One of these is located on the border between Suffolk and Norfolk, where ageyn, nat and sorwe are frequently attested. Two other locations also lie in counties adjacent to Suffolk, where these same words are used, though less frequently, while one is located just west of Norfolk, where nat and sorwe are frequently attested, with seyth only occasionally indicated. The other three locations are scattered throughout the country, but all in the South. Thus, based on eLALME and these features, the text might resemble an Eastern dialect. This ties in with Lydgate’s own Suffolk origin, but also with the name of one of the manuscript’s first owners, John Kyng of Dummowe, as Dunmow lies in Essex.

D. Transmission of text

D1. Transmission

The text survives in 36 manuscripts, thus, as Mooney points out, suggesting its popularity at the time. The oldest manuscript is Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 686 (c. 1430 − 1440). Of the 36 extant manuscripts, 32 are from the fifteenth century, three from the sixteenth century and one from the seventeenth century. Additionally, there are three print versions of the text. This shows the text’s prolonged popularity and use.D2. Witness-specific information

There are many different versions of this poem in the extant manuscripts. Several manuscripts other than Leiden contain additional stanzas, added to either the beginning or the end, concerning other kings, for example the reigns between Alfred the Great and Harold Godwinson, or the subsequent reigns after 1461. These stanzas are not written by Lydgate, but do show the continued use of the poem for political ends.

D3. Scribe

Scribe I of Leiden wrote this text. This scribe is English, from the second half of the fifteenth century, who writes in a cursive hand. He was responsible for most of the texts in this manuscript, including Lydgate’s Fall of Princes − another royally-themed poem.

D4. How was it read/used?

Study has found no notes added to the poem in Leiden. However, there are a few reading aids provided, such as the Latin title at the top, which has been added to the manuscript by the Dutch scholar Franciscus Junius, a sixteenth/seventeenth-century owner. Furthermore, the kings’ names in the margin serve as helpful aids that indicate which king is dealt with in the stanza. These names seem to be the same handwriting as the main text, but they could have been added later as well. These additions would clarify the text more and serve a learners audience.

E. Bibliographical overview:

E1. Bibliography secondary scholarship

Benskin, M., M. Laing, V. Karaiskos and K. Williamson. An Electronic Version of A

Linguistic Atlas of Late Mediaeval English. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh,

2013. http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ihd/elalme/elalme.html

Britannica Academia. “Alexandrine.” Accessed December 14, 2017, https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/alexandrne/5637 (direct link) or

https://login.leidenuniv.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https://academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/alexandrne/5637 (via Leiden proxy)

Bühler, C.F. “Lydgate’s Verses on the Kings of England.” Review of English Studies 9, no.

47 (1933): 47-50. ProQuest. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1293805918?accountid=12045 (direct link) or

https://login.leidenuniv.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1293805918?accountid=12045 (via Leiden proxy)

Gale Encyclopedia of World History: War. Encyclopedia.com. “The Hundred Years’ War

(1337–1453).” Accessed December 14, 2017.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/hundred-years-war-1337-1453

Horobin, Simon. The Language of the Chaucer Tradition. New York: D.S. Brewer, 2003.

Lambdin, Laura C., and Robert T. Lambdin. A Companion to Old and Middle English

Literature. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. eBook Collection

(EBSCOhost).

Mooney, Linne R. “Lydgate's ‘Kings of England’ and Another Verse Chronicle of the

Kings.” Viator 20 (1989): 255-289. ProQuest.

Mooney, Linne R., Adrian C. Barbrook, Christopher J. Howe and Matthew Spencer.

“Stemmatic Analysis of John Lydgate’s Verse Chronicle, ‘The Kings of England

Sithen William the Conqueror’.” Revue d'Histoire des Textes vol. 31 (2003): 277-299.

Mooney, Linne R., Daniel W. Mosser, Elizabeth Solopova, Deborah Thorpe, Daniel Hill

Radcliffe, eds. The Digital Index of Middle English Verse. http://www.dimev.net/

Samuels, M.L. “Some applications of Middle English dialectology.” English Studies 44

(1963): 81-94.

Simpson, James. “John Lydgate.” In A Cambridge Companion to Medieval English

Literature 1100-1500, edited by Larry Scanlon, 205-216. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009.

Van Dorsten, J.A. “The Leiden ‘Lydgate’ Manuscript.” Scriptorium 12 (1960): 315-325.

E2: Link to text in Digital Index of Medieval English Verse

http://www.dimev.net/record.php?recID=5731#wit-5731-36